Alamy

AlamyApollo 11 launched this week in 1969, carrying the first men to land on the Moon. In the months leading up to the historic take-off, Nasa put the crew through gruelling, relentless simulations in order to prepare them – and BBC Tomorrow’s World paid a visit.

“There’s not much room in here, and these couches are very uncomfortable,” said the BBC’s John Parry as he sat suspended upside down, alongside James Burke, in the Apollo space capsule simulator at the Nasa space research centre in California in August 1968. “But it doesn’t matter very much,” he conceded, “because when you are in space your body doesn’t weigh anything at all.”

BBC Tomorrow’s World had gone to see how Nasa was devoting vast sums of money and huge amounts of effort trying to mimic what the astronauts of Apollo 11 would see, hear and experience in space.

In 1962, President John F Kennedy had committed the US to the ambitious goal of landing a man on the Moon, and bringing him safely back to Earth.

To prepare those astronauts for this voyage into the unknown, Nasa had built a complex system of incredibly detailed simulators. These enabled the crew to master the intricacies of the Apollo spacecraft, and for Mission Control to meticulously rehearse every phase of the mission, from launch to lunar landing to re-entry.

The contraption Parry and Burke found themselves strapped into, recreated what it would be like to be inside and fly the command module which was nicknamed Columbia. Equipped with all the same flight controls and displays as the space capsule, it could generate all the responses and readouts that could happen on a mission. It was also designed to have exactly the same “feel” as the ones the astronauts would eventually use so they could develop their muscle memory.

“The spacemen who will be inside here may have to spend as much as 14 days locked up and for the whole of that time, they will take it in turns to do eight hour shifts at this control panel, looking at the dials and the instruments and controlling the switches,” said Parry.

To create the feeling of being in space, Nasa had painstakingly created a 3D scale model of the Earth and an elaborate optical system that projected realistic out-the-window views as both the planet and the Apollo spacecraft rotated for each stage of the mission. The spaceship would need to rotate slowly in order to stop the Sun-facing side from overheating, and the other side freezing from the cold temperatures in space. The astronauts dubbed this manoeuvre “barbecue mode”.

“Every minute motion of the spacecraft is reflected here, and as the prisms turn and roll the astronaut gets a vivid impression of the Earth hundreds of miles below him. Spain and the North African Coastline – it took six artists six months to paint on all the detail by hand, working mostly from satellite photos. Some of the areas on this map are accurate to half a mile,” said Burke.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTo allow the crew to determine the spacecraft’s position and navigate their journey, another television camera projected realistic pictures of the stars in the sky that would be in their field of vision. “They roll gently past Apollo’s window as the craft spins in deep space, 1353 of the most important ones are all the correct size in relation to each other.”

The spacecraft they planned to launch was extraordinarily complex, with a range of intricate systems governing all aspects of the Moon flight, from propulsion and navigation, to communication, electrics and the astronauts’ life support.

Nasa had assembled an army of flight controllers who sat at consoles managing and monitoring the different systems during every second of flight. Many of these flight controllers were young, and had been recruited fresh out of college – the average age was just 27.

“Everything that happens in the capsule in this simulated flight is watched over in this main control room, and another one at the space administration headquarters in Houston, Texas, 1,500 miles away,” said Burke.

“It’s all recorded for study afterwards by both control-room staff as well as astronauts who are trying out the equipment. Short of reproducing the actual physical and psychological stresses of space flight, they have tried to bring realism to everything else here.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThese flight controllers were crucial to the mission. They effectively acted as a team of co-pilots for spacecraft, constantly passing information to the crew, monitoring their life vitals, calculating the exact timings for rocket firings to keep them on course.

“During a simulated flight, control staff are as busy as the astronauts, checking the mass of computerised information,” said Burke.

“[They’re] watching a bank of closed-circuit television monitors and talking, in constant touch with their counterparts in Texas. The wall navigation controls are completely operational; the crew has to cross check every decision with the onboard computer before altering course.”

Ready for anything

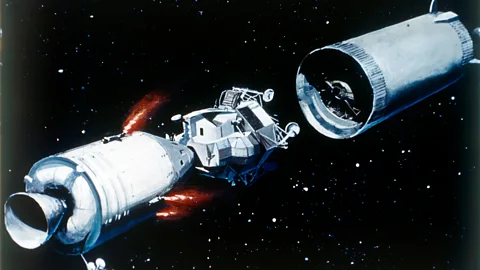

During the actual space flight, the astronauts and the flight controllers would need to be ready for anything, so simulations included every scenario Nasa could think of. Along with practising complex manoeuvres, like docking and undocking the lunar module, Nasa would simulate potential system failures, anomalies and emergencies in order to test the astronauts’ and flight controllers’ ability to remain calm and work together, communicate accurately and make sound decisions quickly under pressure.

“You have a training team, led by a simulation supervisor, and their job is to come up with mission scenarios that are utterly realistic and will train every aspect of the crew and controllers’ and flight directors’ knowledge. Training was about as real as you could get. You would get the sweaty palms. It was no longer training – it was real. The same emotions, the same feelings. The same adrenaline would flow,” he said.

These intense, exhausting training simulations worked to bond the astronauts, the flight controllers and Mission Control, honing their ability to innovate strategies when things suddenly went wrong, and weeding out people who couldn’t handle the pressure and stress.

“In a day’s work, we would exercise this 10 or 12 times a day. Run it, debrief it, turn it around, run another one,” former Apollo flight controller John Aaron told the BBC in 2019.

“When you get out of the room at the end of the day you are drained. I used to tell people, you know if you can survive the simulations, the mission is a piece of cake because you are not usually working on 20 problems at once. Maybe one.”

The simulator of the lunar module (nicknamed Eagle) proved particularly crucial. It enabled Armstrong and Aldrin to repeatedly practise their descent and landing on the Moon – on the mission, Mike Collins stayed behind, orbiting in the command module.

The landing required precise manual control because of the unpredictable surface of the Moon. Running through the simulations, the flight crew were able to gameplay what they would do if there was an engine malfunction or a landing gear problem.

These gruelling training simulations enabled the astronauts and the flight controllers to understand the different systems and machines so intuitively that when it came to the actual landing in 1969, they were able to make the right decision, despite receiving warning alerts from them.

As former Nasa flight controller Gerry Griffin told Witness History in 2019: “The final phases of the descent of Apollo 11 were kind of fraught, we had two computer alarms, a 1202 and a 1201 alarm saying that the computer was being overworked, so it was not a good thing.

“Luckily on the last simulation before we actually launched the mission, we had seen them,” said Griffin, “and when it came up on the flight, the guys knew more about it. They took a quick look to make sure all the guidance was correct, but quickly gave them a ‘go’. By the way, the young man who made that call was in his 20s.”

Just minutes later, Armstrong was similarly able to make a split-second call when he could see from the window of Eagle that the landing site selected by Nasa was actually strewn with craters and huge rocks. Despite running out of fuel, and feeling the pressure to abort, he decided to manoeuvre to try and find a smooth place to land.

“We were watching that and it was nerve-wracking. It was in Neil Armstrong’s hands at that point,” said Griffin. “And I never will forget when Buzz Aldrin said ‘we are picking up some dust’. That’s when I thought we are going to make it, we’ve got an engine blowing dust off the Moon.

“Neil told me one time, ‘this is like an automobile. When it’s on empty, there is a little bit left in the tank.'”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter the safe landing and return of Apollo 11, the Nasa lunar programme continued until 1972, landing on the Moon another five times. Now, the race to send humans to the Moon is hotting up again – this time with vastly more developed technology. Nasa’s Artemis astronauts are aiming for a 2026 landing, and China is saying it will send people to the Moon by 2030.

“You know today, 50 years later, I think the historical significance has more of an impact on me now than it did then,” said Griffin. “Do you realise what we did and with old technology, and it kind of amazes me. It amazes me still that we were able to do what we did.”

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.