Courtesy of Cannes

Courtesy of CannesAlong with the red carpet, sunburned film critics and warm rosé, awkwardly long standing ovations at premieres are one of the Cannes Film Festival’s defining traditions.

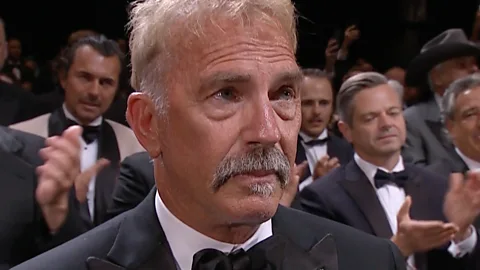

Kevin Costner had tears in his eyes during the seven-minute standing ovation at the premiere of his latest Western, Horizon: An American Saga, at the Cannes Film Festival. The chances are that he was overwhelmed by the enthusiastic reception: Horizon is, after all, a passion project that Costner starred in, directed, co-wrote, produced and financed himself. But it’s possible that he was just bored to tears. Can you imagine how exhausting it must be to nod and smile and listen to people clapping for seven whole minutes?

But it could have been a lot worse – or, depending on your perspective, a lot better, because weirdly long standing ovations are one of Cannes’ defining traditions. Along with parties in beach bars, warm rosé wine, and long queues of sunburnt critics, these marathon lovefests are one of the elements that give the venerable festival its je ne sais quoi. In 2021, the opening film was Leo Carax’s Annette, starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard. Five minutes into the standing ovation, Driver lit up a cigarette to pass the time. This year, the applause received by David Cronenberg’s The Shrouds was described in the press as “subdued” and “lackluster” – but it still went on for more than three minutes.

Standing ovations aren’t unknown at other film festivals, of course, but they have never had the same cachet elsewhere. At Cannes, the premieres – or “Official Screenings” – are held in the Grand Théatre Lumiere, which seats more than 2,000 people. The rule is that everyone has to be in evening dress, and there is a red carpet flanked by rows of photographers to add to the buzz. Another key factor is that as soon as the closing credits roll, a cameraperson dashes into the Lumiere and points a camera at the main members of the cast and crew; close-up footage of them looking proud / tearful / embarrassed / all of the above is then shown on the big screen. This has the dual effect of encouraging the audience to keep clapping, and making the ordeal even more awkward for the grimacing directors and stars. This footage is also the source of many a bored superstar meme on social media. It’s small wonder that when Andrea Arnold’s Bird had its inevitable ovation last week, Arnold said: “Thank you, this is really lovely, but I really want to go and party right now.”

In general, there does seem to be a connection, however tenuous, between the length of the ovations and the quality of the films. The longest on record was for Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, which kept people clapping for a hand-burning 22 minutes in 2006, followed by 20 minutes for Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 in 2004. Both films were major successes, so you can see why newspapers and magazines include the length of these ovations in their write-ups, and why advertisers include the statistic in their promotional material. But there are plenty of exceptions to the rule. Lee Daniels’ The Paperboy received a 15-minute standing ovation in 2012, and went on to be one of the year’s most notorious flops.

Bear in mind, too, that all of these figures are approximate. A story in The Hollywood Reporter this week noted that when Steven Spielberg’s ET The Extra Terrestrial rounded off Cannes in 1982, it garnered a “six-and-a-half-minute standing ovation”, but by the time Spielberg was back on US soil, he was hearing that it had lasted 20 minutes. Today, when these events are recorded on dozens of phones, you might assume that such inflation would be impossible. But that seven-minute standing ovation for Horizon that I mentioned above? It’s also been reported in the press as lasting 10 minutes and 11 minutes.

Charles McDonald, a Cannes veteran and one of Britain’s most respected film PRs, categorises the tradition as “a fun diversion that means very little in reality”. But wouldn’t he want a film he was representing to get the full 22-minute treatment? “Of course a warm response is to be welcomed, especially by the film-makers,” McDonald tells the BBC, “but the truth is that the key screenings are the press screenings – they are the root of how a film is perceived and reported.”

So why do audiences at Cannes’ black-tie premieres stay on their feet for so long? My own theory is that the applause isn’t entirely for the films, nor is it entirely for the film-makers in attendance. It’s for the whole experience – the all-too-rare communal experience of seeing a brand-new film in a vast cinema jam-packed with other people who are as excited about it as you are. Let’s face it, it’s not often that you dress in your swankiest clothes to see a film; it’s not often that you see that film at a huge-yet-exclusive event which attracts the media; and it’s not often that you have the chance to congratulate the makers of that film the moment you have finished watching it.

Audiences can celebrate the actors in plays with a standing ovation every time they go to the theatre, but when do we ever get the opportunity to show our love for film-makers, for cinema itself, and for one of the world’s most prestigious film festivals? Most people won’t participate in that shared moment more than once or twice in their lives, so you can’t blame them if they make it last as long as they possibly can – whether Adam Driver likes it or not.